|

| Advertisement |

Let’s talk about some of the most influential women in medicine.

Elizabeth Blackwell

You might've heard of Elizabeth Blackwell, who made history in 1849 when she became the first woman in America to earn a medical degree. After training as a midwife and working for several years in Europe, she eventually lost sight in one eye — but that didn't stop her from pursuing a career in medicine. She returned to New York City to practice, but no one would hire a female physician. So Blackwell decided to open her own dispensary in a house's rented room.

Several years later, in 1857, Blackwell opened the New York Infirmary, which focused on caring for the poor. It had its own medical institution so women could get the training and experience they needed as physicians — but couldn't get from other male-dominated hospitals. Blackwell was a tireless advocate for improving medical education for women and championed gender equality in medicine. Can we all agree she totally kicked ass?

National Library of Medicine (NLM) / NIH / Via commons.wikimedia.org

Susan La Flesche Picotte

Susan La Flesche Picotte overcame all of the odds to become the first Native American woman in the United States to get a medical degree. After graduating from the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1889, Picotte returned to the Omaha reservation to care for members of her tribe and was the only physician at a government-run boarding school that served thousands of people.

In addition to providing medical care, Picotte also gave financial, legal, and spiritual guidance to members of her tribe — all while battling a terminal illness. Picotte lobbied for the prohibition of alcohol on the reservation and improving living conditions, and eventually opened a hospital on the reservation several years before her death. During her career, Picotte cared for thousands of Native and non-Native patients across Nebraska, leaving a lasting legacy.

National Library of Medicine (NLM) / NIH / Via commons.wikimedia.org

M. Joycelyn Elders

Joycelyn Elders made history when she became the first board-certified pediatric endocrinologist in Arkansas (not the first woman, the first ONE), where she practiced for 20 years and researched juvenile diabetes. She went on to become the head of the Arkansas Health Department, where she campaigned to increase family planning clinics and sexual education; this helped relatively conservative Arkansas to mandate a K–12 sex ed and substance abuse prevention program.

President Bill Clinton appointed Elders as the US surgeon general in 1993, making her the first black doctor and the second woman to hold the position. As surgeon general, Elders was outspoken about her progressive policies, such as drug legalization to reduce crime and the distribution of contraceptives in schools. The conservative backlash led Elders to resign after 15 months, but she remains a major influence in public health and sexual education.

NIH / Via commons.wikimedia.org

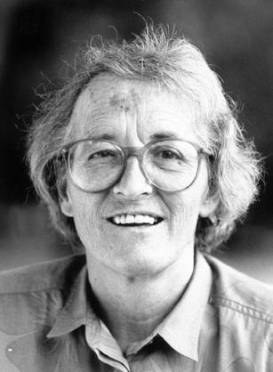

Mary Steichen Calderone

Mary Calderone didn't enter medical school until she was 30 and already had children (and an acting career behind her), but that did not slow her down from becoming a legendary physician and advocate for sexual health and education. After receiving her medical degree, Calderone got a master's in public health from Columbia and in 1953 she became the medical director of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America, where she championed progressive ideas about human sexuality and sexual education.

Calderone later founded the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States and worked tirelessly to educate young people about safe sex and empower them with the tools to stay healthy. In a time when sex was still a relatively taboo topic, Calderone fought to help people have healthier and happier sex lives. Her efforts led to a greater awareness and improved education about sexual health. Thank you, Dr. Calderone!

Smithsonian / flickr.com / Via commons.wikimedia.org

Patricia E. Bath

Patricia Bath began her influential medical career when she became the first black doctor to complete a residency in ophthalmology at New York University. After practicing in Harlem and observing higher rates of blindness in people of color, Bath introduced a new discipline of medicine — community ophthalmology — to deliver primary care in underserved and minority communities.

Bath then became the first female ophthalmologist at UCLA and she didn't stop making history there — Bath went on to invent a new device to remove cataracts from the eye, called the Laserphaco Probe, which made her the first black woman to receive a medical patent. Her brilliant invention has helped restore vision to people all over the world. Bath is also an advocate for preventing and curing blindness and founded the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness in Washington, DC. Thank you, Dr. Bath!

National Library of Medicine (NLM) / NIH / Via cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was a Swiss-born American physician who made major contributions to the field of psychiatry. As a teenager, she left home to volunteer around Europe and help communities devastated by World War II. After she received her medical degree in 1957, Kübler-Ross moved to the US, where she worked in Chicago as an assistant professor of psychiatry at Billings Hospital. It was during her work with psychiatric patients that Kübler-Ross started focusing on the treatment of terminally ill and dying patients suffering from end-of-life anxiety or depression, who she felt were overlooked by many doctors.

Kübler-Ross changed the way people talked about death by advocating for improved transparency, communication, and care at the end of life. In 1969, she published one of the most important psychological studies of the 20th century, On Death and Dying. In the book, she described the five stages of grief in those who are dying: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. The five stages, or the Kübler-Ross model, became an important tool for professionals to better understand and treat dying patients. Kübler-Ross and her contributions have had a lasting impact on the field of psychiatry. And we're all better people for it.

National Library of Medicine (NLM) / NIH / Via cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov

Marilyn Hughes Gaston

Marilyn Hughes Gaston received her medical degree from the University of Cincinnati, and later went to Philadelphia General Hospital to research sickle cell disease (SCD), a potentially fatal inherited blood disorder that's more common in people of Middle Eastern, Asian, Indian, and and African descent. She published a groundbreaking study on SCD in 1986 that proved that babies need to be screened for the disease at birth and given preventive antibiotics to avoid sepsis. The study led to a nationwide, federally funded screening program for newborns.

In 1990, Gaston became director of the Bureau of Primary Health Care in the US Health Resources and Services Administration, where she dedicated her work to improving medical care for poor and minority populations. During her career, Gaston was committed to improving the health of minority populations and people living in poverty, and remains an incredibly influential figure in American medicine.

Maryland Archives / Press Office / Via msa.maryland.gov

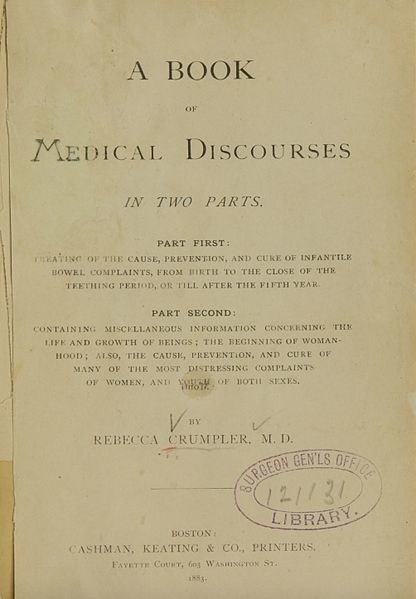

Rebecca Lee Crumpler

After working as a nurse in Massachusetts, Crumpler went to New England Female Medical College, where she became the first black woman to earn a medical degree and become a doctor in the US. This happened in 1864, and we'd like to point out that that was in the middle of the Civil War.

Crumpler then published A Book of Medical Discourses, about her own career and family medicine, making her one of the first people of color to publish in the medical literature. Crumpler then went to Richmond, Virginia, where she worked with the Freedmen's Bureau to deliver health care to freed slaves who otherwise had no access to hospitals or clinics. There are no surviving photos or images of Crumpler, but her book remains an important testament to her legacy in medicine. Yes, she definitely broke barriers, made history, and all-around kicked ass.

NIH / Via commons.wikimedia.org

For more information on women in medicine, visit the National Library of Medicine's Changing the Face of Medicine exhibit online.

0 comments: